Inmates at Milan’s biggest penal complex have given new existence to the remnants of Europe’s fatal migrant disaster.

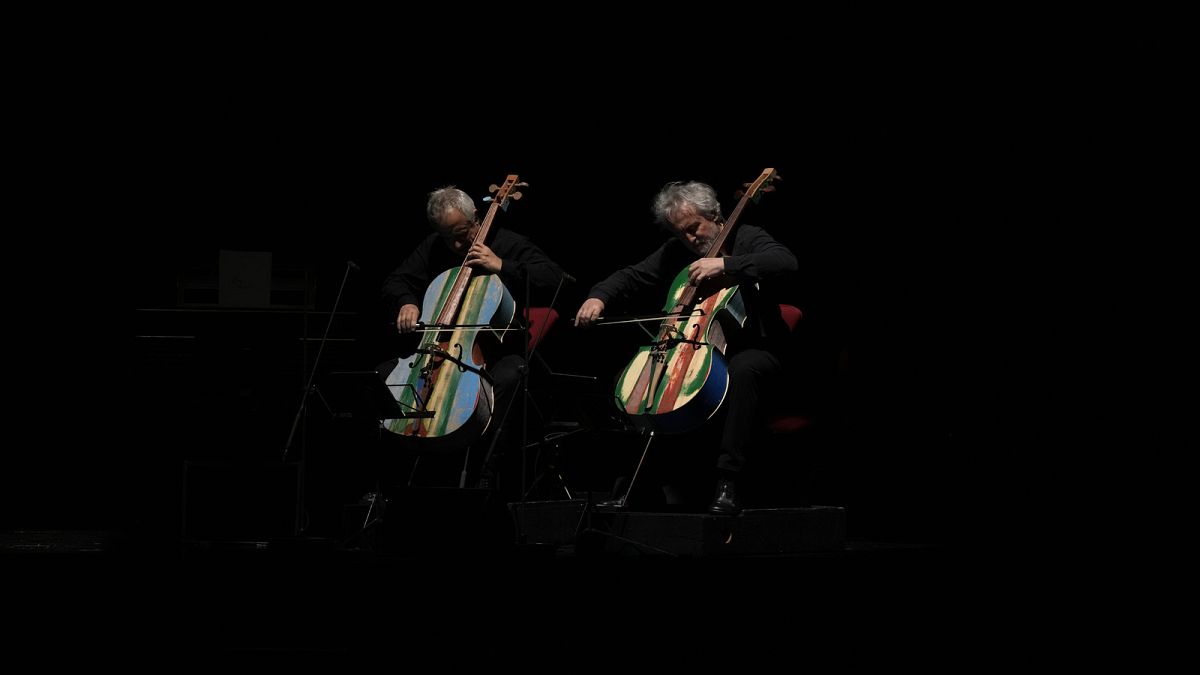

As the Orchestra of the Sea debuted at Milan’s famed Teatro alla Scala, the violins, violas and cellos carried stories of desperation and redemption.

Inmates from Milan’s biggest penal complex were bending, chiseling and gouging the wooden from battered boats utilized by human smugglers to deliver migrants to Italy – remodeling them into tools.

The mission, dubbed Metamorphosis, specializes in remodeling what differently could be discarded into one thing of worth to society: rotten wooden into fantastic tools, inmates into craftsmen, all beneath the main of rehabilitation.

Two inmates had been granted depart to peer the Orchestra of the Sea’s debut live performance this Monday. The live performance featured 14 prison-made stringed tools enjoying a program that incorporated works by means of Bach and Vivaldi.

The two prisoners sat within the royal field along Milan Mayor Giuseppe Sala.

“I feel like Cinderella,” stated Claudio Lamponi, an inmate. “This morning I woke up in an ugly, dark place. Now I am here.”

Far from the stately La Scala opera space, the Opera penal complex on Milan’s southern edge has over 1,400 inmates, together with 101 suspected Mafia individuals held beneath a strict regime of near-total isolation.

Other inmates, like Nikolae, who joined Lamponi at La Scala, are allowed extra latitude.

Since becoming a member of the penal complex’s device workshop in 2020, Nikolae – who declined to provide his complete title and prefers to skim over the costs that landed him in penal complex a decade in the past – has transform Opera’s grasp craftsman, graduating from crude tools created from plywood to harmonious violins worthy of La Scala’s level.

“That’s how I started to talk with the wooden,” Nikolae said recently in the prison workshop, which is filled with the smell of wood chips amid the rows of chisels and the faint hum of a jigsaw. “I started with very poor materials, and they saw I had good dexterity.”

Working on the instruments four to five hours a day gives him a sense of tranquility, he said, to reflect on “the mistakes I made” and skills that allow him to consider a future. “I am gaining self-esteem,’’ he said, “which is no small thing.”

One “graduate” of the prison workshops has completed his sentence and is working as a master luthier at another prison, in Rome.

“I hope one day, I can be recuperated, like this violin,” Nikolae said.

The boats arrive at Opera much as they were seized, still containing remnants of the migrants’ lives, and with them a reminder of the 22,870 migrants that the UN says have died or gone missing on the perilous central Mediterranean crossing since 2014.

A shoulder bag with a disposable diaper, baby bottle and infant shoes sits on one prow alongside tins of anchovies and tuna from Tunisia and many plastic sandals.

Each instrument takes 400 hours to create, from disassembling the boats to the finished product.

“These instruments, which have crossed the sea, have a sweetness that you could not imagine,’’ said cellist Mario Brunello, a member of the Orchestra of the Sea. “They don’t have a story to tell. They have hope, a future.”

The House of the Spirit and Arts Foundation that first brought workshops for making stringed instruments to four Italian prisons a decade ago hopes the concert at La Scala will be the beginning of a movement to bring Orchestra of the Sea performances first to the southern European countries bearing the brunt of migration, then to the northern capitals that hold the most sway in migrant policy.

“The beauty is that music overcomes all divisions, all ideologies, goes to the heart and soul of people, and one hopes that it makes people think,” stated basis president Arnoldo Mosca Mondadori. “Politicians wish to recall to mind this drama.”